About the Ikaahuk Archaeology Project

Inuvialuit are Inuit of Canada’s western Arctic. Their rich history is rooted in the lands and waterways of their homeland. Inuvialuit and archaeologists have different ways of learning about the past. The Ikaahuk Archaeology Project (IAP) brings together Inuvialuit and archaeological approaches to understand and share the history of Banks Island, known as Ikaahuk or Ikaariaq in Inuvialuktun. Our team, based at the University of Western Ontario (in London, Ontario) includes university researchers and Inuvialuit community members. Our goal is to do archaeology that matters to and includes Inuvialuit.

If you have a connection to Sachs Harbour or an interest in Inuvialuit history, we built this site to share our results with you. Come on in and explore! |

|

Community Archaeology and the IAP

Community archaeology aims to open up the research process to bring more voices into archaeological interpretations. In the North, it grew out of Inuit concerns about being excluded from traditional archaeological research. This approach, embraced by the Ikaahuk Archaeology Project, aims to respect and apply the experiences and knowledge of Inuit communities and collaborate with them throughout the research process.

Dr. Lisa Hodgetts from the University of Western Ontario, started the project in 2012, building on her earlier work with community members in Aulavik National Park in 2008-9. Initially, it focused on questions about past land use on the Island, while looking to the community for direction. Community members in Sachs Harbour have since shaped the research path. They shifted the focus away from excavation because traditional Inuvialuit teachings caution against disturbing archaeological sites. The project now focuses on applying community knowledge (through an interactive map) and making it easier for community members to find out about archaeological sites and artifacts from our work and that of other archaeologists (using 3D models, a community visit to Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre, and this website). Going forward, we hope to continue to work with Inuvialuit communities to study and share their archaeological collections that are held in museums outside of their traditional territories. Check out the Inuvialuit Living History Project to see what team members are working on now.

Dr. Lisa Hodgetts from the University of Western Ontario, started the project in 2012, building on her earlier work with community members in Aulavik National Park in 2008-9. Initially, it focused on questions about past land use on the Island, while looking to the community for direction. Community members in Sachs Harbour have since shaped the research path. They shifted the focus away from excavation because traditional Inuvialuit teachings caution against disturbing archaeological sites. The project now focuses on applying community knowledge (through an interactive map) and making it easier for community members to find out about archaeological sites and artifacts from our work and that of other archaeologists (using 3D models, a community visit to Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre, and this website). Going forward, we hope to continue to work with Inuvialuit communities to study and share their archaeological collections that are held in museums outside of their traditional territories. Check out the Inuvialuit Living History Project to see what team members are working on now.

Archaeological Timeline for Banks Island

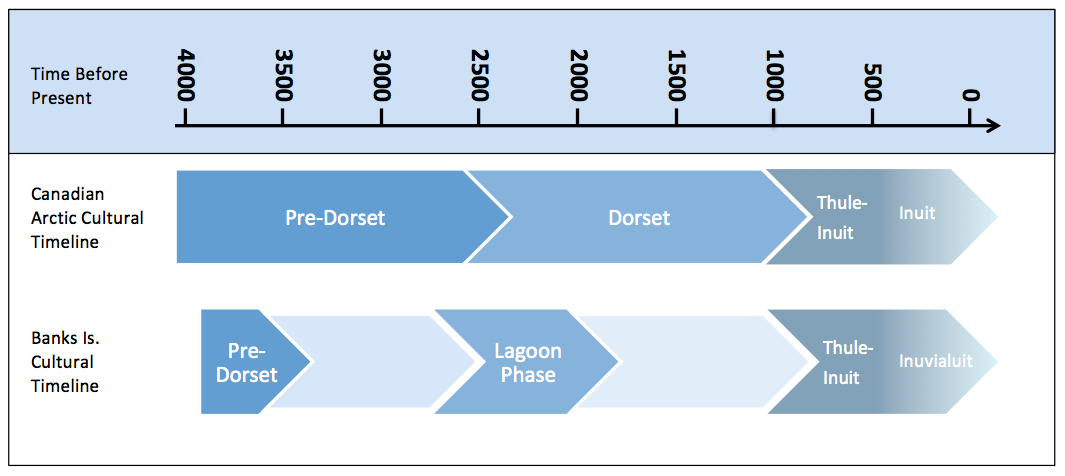

Throughout history, the people of Banks Island have left their mark on the landscape, leaving the remains of houses, tent rings, caches, graves, and kayak rests. Archaeologists read their stories from these things. When thinking about the past, archaeologists often focus on time, asking when things happened. Inuvialuit tend to focus more on place, asking where things happened. Below is a timeline of human history on the island, representing an archaeological point of view. The interactive map presents a more Inuvialuit-centred approach to this history.

Inuvialuit attribute some of the structures above to the Tuniit, or Little People (also called the Pulayuqat or Inuagulit in the Kangiryuarmiutun dialect). Archaeologists call the Tuniit “Pre-Dorset” and “Dorset.” According to archaeologists, Pre-Dorset muskox hunters were the first people on the island (from roughly 3800-3600 years ago). After they abandoned the island, another group arrived around 2500 years ago. Archaeologists place this group within the “Lagoon Phase,” which was part of a broader cultural shift as earlier Pre-Dorset groups developed into Dorset groups across the arctic. The island was once again abandoned after the Lagoon Phase.

The ancestors of the Inuvialuit came to Banks Island when they began to migrate from Alaska into the Canadian Arctic around 800 years ago. Archaeologists call them “Thule-Inuit.” A limited number of early Thule-Inuit sites have been found on Banks Island, some of them among the earliest Inuit sites in Canada [2],[3]. While archaeologists once thought Banks Island was abandoned and reoccupied several times after Thule-Inuit arrived, mounting evidence suggests more continuous use. Beginning in the 1920s, many of the Inuvialuit families that live in Sachs Harbour today came to Banks Island from the mainland and neighbouring Victoria Island to hunt and trap for furs.

Inuvialuit attribute some of the structures above to the Tuniit, or Little People (also called the Pulayuqat or Inuagulit in the Kangiryuarmiutun dialect). Archaeologists call the Tuniit “Pre-Dorset” and “Dorset.” According to archaeologists, Pre-Dorset muskox hunters were the first people on the island (from roughly 3800-3600 years ago). After they abandoned the island, another group arrived around 2500 years ago. Archaeologists place this group within the “Lagoon Phase,” which was part of a broader cultural shift as earlier Pre-Dorset groups developed into Dorset groups across the arctic. The island was once again abandoned after the Lagoon Phase.

The ancestors of the Inuvialuit came to Banks Island when they began to migrate from Alaska into the Canadian Arctic around 800 years ago. Archaeologists call them “Thule-Inuit.” A limited number of early Thule-Inuit sites have been found on Banks Island, some of them among the earliest Inuit sites in Canada [2],[3]. While archaeologists once thought Banks Island was abandoned and reoccupied several times after Thule-Inuit arrived, mounting evidence suggests more continuous use. Beginning in the 1920s, many of the Inuvialuit families that live in Sachs Harbour today came to Banks Island from the mainland and neighbouring Victoria Island to hunt and trap for furs.